Clinical Pearls: Pleural Effusions

In a nutshell, this is fluid where it isn’t supposed to be. The range of effects upon the critical care patient is vast though. In the early days I had a hard time identifying it, grading it’s severity, and determining when and how to do something about it. One of the worst feelings as a nurse practitioner is not having a plan to present. The cool thing about pleural effusions though, is that’s once it’s broken down it is kind of straight forward. Learn how I mastered the approach to diagnosing and treating pleural effusions.

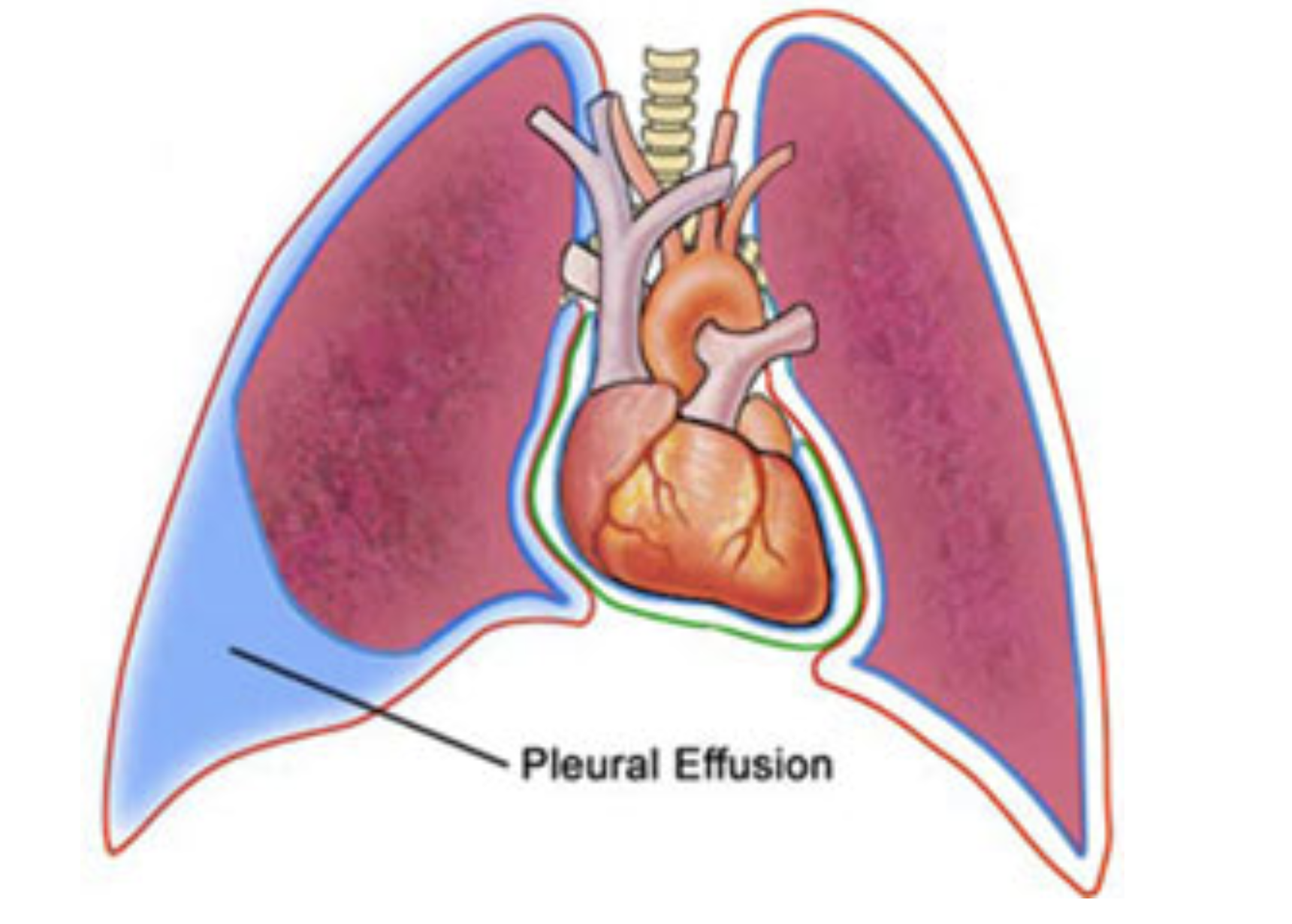

Image courtesy of https://healthinfo.healthengine.com

Diagnosing.

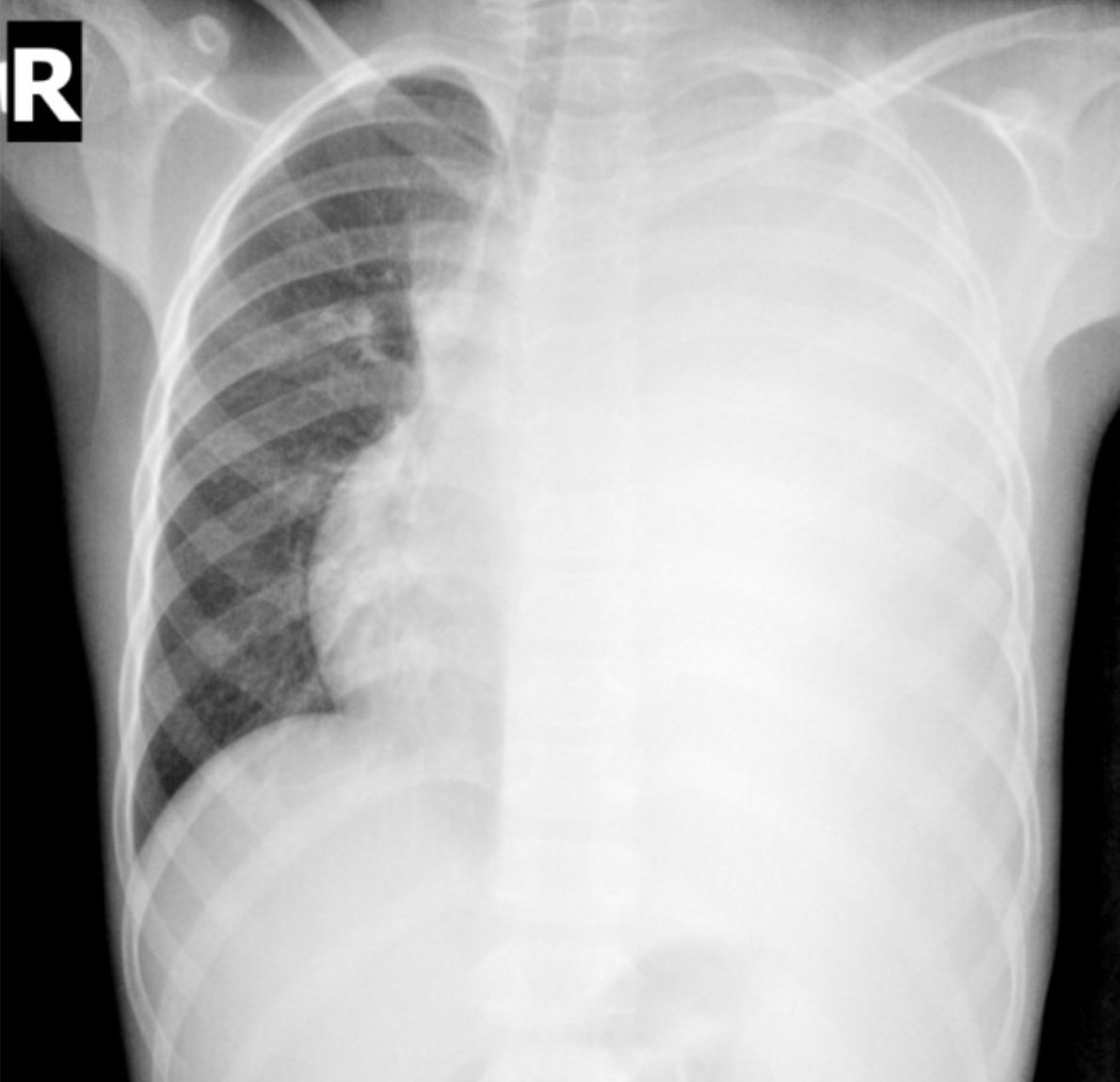

When looking at images it comes down to understanding where the fluid is located. With a pleural effusion it is trapped between the visceral and parietal layers of the pleura, so the “sac” surrounding the lungs. Patients will say they have fluid in the lungs but this isn’t physiologically correct. The fluid is impeding the lungs ability to expand or inflate. Since it is well, fluid, it has a gravitational effect. It will lay like water would - dependently (complex collections like empyema or loculated effusions are less mobile). So we see it in the bases of the lung (if upright) or the posterior segments (if supine). Therefore, depending on the position of the patient when the image was taken will determine where you will see the opacity. It will have a more even, scooped out appearance. Think, water in a ziplock bag look. This helps you distinguish it from an infiltrate (more irregular, possibly spiculated, “sticky” appearance) or atelectasis (more wedge shaped, probably with rib space narrowing/contraction and trachea being pulled to it). Pleural effusions, if pronounced and more unilateral, may have tracheal deviation away from the side of the fluid collection. Below are some CXR and CT scans. All photos are not my own and credit is given to the source. If you want more image interpretation help I strongly recommend https://www.radiologymasterclass.co.uk

Differentiating.

Before you can get to treatment you need to further define what type of pleural effusion is present. There are essentially two categories: exudative and transudative. You have to decide if a diagnostic thoracentesis is warranted to make this differentiation. Light’s criteria is fairly definitive and I use it often to guide decision making. https://www.omnicalculator.com/health/lights-criteria

Treating.

Management of the problem should be targeted. Review the common causes of each type and come to a most likely etiology. For example, if you have an exudative effusion in a pt that presents with complaints of increased cough, leukocytosis, and fever you likely have a parapneumonic effusion. Cultures and antibiotics are mainstays, possibly a chest tube. Conversely, if you have a transudative effusion and the clinical picture fits with heart failure your focus should be on diuresis, a chest tube will just continue to drain without a “fixable” solution. For a patient that is hypoxic or failing to wean from the vent I am more aggressive about actively trying to alleviate the fluid burden. If the aforementioned HF patient has significant pulmonary compromise I would start with trying to diurese and then consider a therapeutic thoracentesis. Any time you put a needle into a person you assume risk, so although this is a common procedure, I ALWAYS weigh the risk / benefit.